Our pewter knucklebones are copies of late medieval playthings in our collection. They are a stylized version of a real knucklebone, (talus in Latin) taken from the hind leg of a sheep. Real knucklebones have been used in games since antiquity, and Greek and Roman art, as well as in late medieval paintings, show people playing with them. Two types of game can be played with them – a game of dexterity and a gambling game.

Cock-All, A Game of Dexterity

Cock-All is a game related to the modern game of jacks. It has many names in English, including hucklebones, knucklebones, and dabs. There is no known account of exactly how it was played in the Middle Ages, but a large number of versions have been collected by folklorists over the last two centuries, and those versions, together with historical paintings and statues, give us an idea of the roots of the game.

The basic idea is that you do fancy tricks with five knucklebones, like throwing one in the air and picking up the others before you catch it again, throwing one in the air and pushing the others through an arch made by the fingers of your other hand before catching, etc. If you have played jacks, you can imagine that it is much tougher when the “ball” is thrown in the air – and comes right back down – rather than bouncing.

The most convenient source of information on the variants of cock-all that have described is Alice Gomme’s Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland. Here is a (relatively) easy one to get started with:

This game can be practiced by yourself. When played against a partner, you play until you make a mistake and then the knucklebones go to the other person. The first person to get all the way through all the tricks without a mistake wins.

Trick 1: Play with 5 knucklebones. To start, hold all five in your palm. Throw them in the air and, turning your hand over quickly, catch all five on the back of your hand. Then do the reverse: flip them up in the air from the back of your hand and catch them in your palm.

Trick 2: *Throw four of the knucklebones on the ground. Throw the fifth in the air and pick up one of those on the ground before catching the (rapidly descending) one. Repeat until you have picked up all five. *Throw the four on the ground again. Throw the fifth in the air and pick up two; repeat. *Throw down your four, throw the fifth up and pick up one. Throw again and pick up the remaining three. *To finish the trick, throw down all four, throw the fifth up and pickup all four before catching the fifth. Repeat Trick 1.

Trick 3 is Trick 2 in reverse: *Holding all five knucklebones, throw one in the air. Place one of the remaining ones on the ground before catching the fifth. Don’t just drop it – set it down. Repeat one by one until all four are on the ground. Pick up all five; throw one in the air and set down two. Repeat. *Pick up all five; throw one in the air and put down one. Throw again and put down the other three. * Pick up all five; throw one in the air, and place the remaining four on the ground. Repeat Trick 1.

That’s it – you’ve done it!

Gomme, Alice. The Traditional Games of England, Scotland, and Ireland; With Tunes, Singing-Rhymes, and Methods of Playing… London, D. Nutt, 1894-1898. Reprinted – New York, Dover Publications, 1964.

The Ludus Talorum

Carolus: Now stake down thy stake.

Quirinus: Let us try for nothing.

C: Wilt thou learn so great an art for nothing?

Q: But it is an unequal match between a cunning gamester, and one that is unskillful.

C: Why, but the hope of winning, and the fear of losing, will make thee mind better.

Erasmus’ Colloquies

We know from Ovid, Martial and Suetonius that the Greeks and Romans played a gambling game with knucklebones. The rules are not certain, but several people have “reconstructed” the game based on clues in the ancient authors. The first person to publish his reconstruction was the Dutch humanist Desiderius Erasmus, in his Colloquies (published in Latin in the 1520’s). Here’s how he says to play:

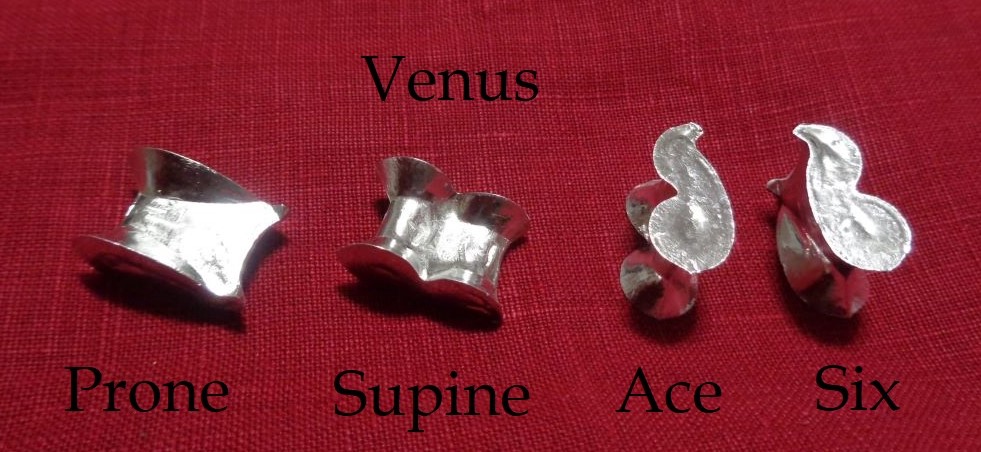

In this game, the different sides of the knucklebones (or tali) have different values. There are four sides: two sides are curved and two flat. One of the curved sides has a deep depression or cup; the other has a smooth slope (these two sides come up more frequently than the other two). Erasmus quotes Aristotle in calling these supine and prone; think of your hand by analogy: if the palm is up and cupped, it is supine; if the back of the hand is up, it is prone. (Erasmus then draws a parallel with people having sex, but we will not wander into that type of vulgarity here.) The two flat sides are mirror images of one another; the one that looks like an S is called the ace (or dog) and the side that looks like a Z is called the six. (For the purist, we should note that in real knucklebones these two sides are not mirror images of one another and there is a difference in the frequency with which they come up. The medieval pewter knucklebone we copied has two flat sides, so we have simply assigned the ace and the six. You can go chase down two sheep and take the four knucklebones you need and play next week or you can use these pewter tali and take money from your buddy right now.) The ace is unlucky; the six is lucky.

The game is played by two people. They take turns throwing down four tali. Each throws them down three times, then passes them to the other person. A game consists of three rounds, each of which ends by one of the players winning the pot. The players must agree at the beginning of each game what coin they are playing with; you may want to use pennies to begin with, since the pot can become quite substantial before the winning combination is thrown.

To begin, one of the players throws the four tali. For every ace (S face) that is thrown, the thrower must put one coin in the pot. For every six (Z face) that is thrown, the other player must put one coin in the pot. (One man’s good fortune is another man’s evil.) No penalty is assessed for the prone and supine faces. Each player throws three times, passing the dice back and forth as the pot grows. The winning throw is called the Venus: each talus shows a different face, one prone, one supine, one ace, and one six. The person who throws the Venus takes the whole pot. When three Venuses have been won, the game is over. (A variant that Erasmus suggests is that the person who throws the dice puts in a coin for every ace and takes one out for every six he throws; the other player does nothing until it is his turn. This makes the pot smaller, but reduces the number of coins you need to have on hand.

Erasmus’ Colloquies were first translated into English in 1671. Nathan Bailey translated them again, in 1725; you can read the 1744 edition of his translation at https://archive.org/details/allfamiliarcollo00eras

Check out (and maybe buy!) our knucklebones!