Many medieval pewter pieces had a central figure in a frame or some other openwork that let you see straight through the piece. Here is a small selection of real pieces from our collection.

And here are some shown in contemporary paintings: on the left. St. Roch, c. 1480. On the right, St. Josse, c. 1500.

In some openwork pieces you see the clothing of the wearer (or whatever else the item is attached to) through the openings, as with St. Roch’s middle sign. In others, there is a backing attached to the pewter, and you see the foreground figure against the backing instead – just as the backing of St. Josse’s larger pilgrim sign shows, rather than his hat.

Pewter items that were designed to take a backing have little tongues or fingers sticking out from the edge. You fold these tongues over to hold the backing in. Medieval castings with tongues almost always have them bent in – whether the backing is still there or has been lost. Here’s a Flemish pilgrim sign with the Virgin inside a banner. The arrows point to four of the ten (maybe eleven) folded over tongues that once held in a backing.

And here is a partial pilgrim sign from Canterbury (now in the Museum of London). The upper tongue on the left is sticking out, bent down a little, but in the same position it was cast in. The lower tongue is folded in.

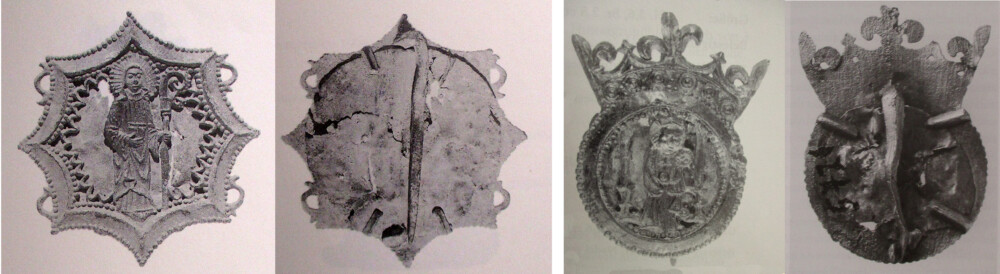

A small number of medieval pewter signs, brooches, and pendants still have their original metal backings. Here are examples, fronts and backs, from the Musee de Cluny (left) and from the Yper City Museum (right).

Museum and collection records seldom identify the metal backing materials fully or accurately . They are frequently described (I’m translating to English here) only as “metal” or sometimes, “a backing plate,” or “a sheet.” When the metal is identified, we still have to be cautious. A backing identified as “tin,” “lead,” or “pewter,” may actually be any of those metals or alloys, unless the piece has been subjected to analysis by radiography, X-ray fluorescence, optical emission spectroscopy, etc. Usually someone just guessed based on color, oxidation, corrosion, damage, or signs of fabrication.

Enough backings have been reliably identified that we can be sure – at a minimum – that copper and tin (or tin alloys) were used. This banner- shaped pilgrim sign for St. Job at Wezemaal (HP 3, no.2369; Kunera 16449) dated 1525-1575, has a backing identified as copper.

The backing of a round brooch showing a king and a bishop holding up a city gate or other structure between them (HP 2, no.1687; Kunera 06817), dated to 1383, in the Yper City Museum has been identified as tin.

Many extant pieces have folded over tongues, but no backings. This strongly suggests that their backings were materials that degraded over time. (A small number of other materials are sometimes held into pieces with pewter tongues, including mirrors and wood, but they are uncommon. We will discuss them in the future.) If you were re-creating one of these objects, it would be reasonable to make a backing of parchment, paper, or cloth (perhaps glued to parchment or card). Any of these might also have been painted – either as a solid color or embellished with a decorative pattern. As we will see in a moment, patterned metal backings were used, although infrequently. I do not know of any direct evidence for the materials of the absent backings, so this is speculation, but it seems reasonable. It also seems possible that some pieces were offered with a choice of metal or parchment/textile backings – presumably at different price points.

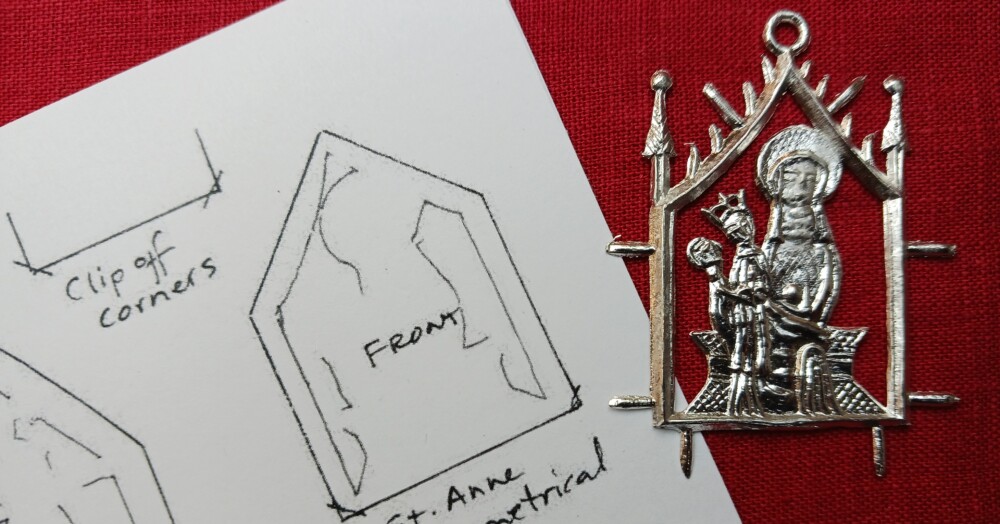

Our pieces with backings

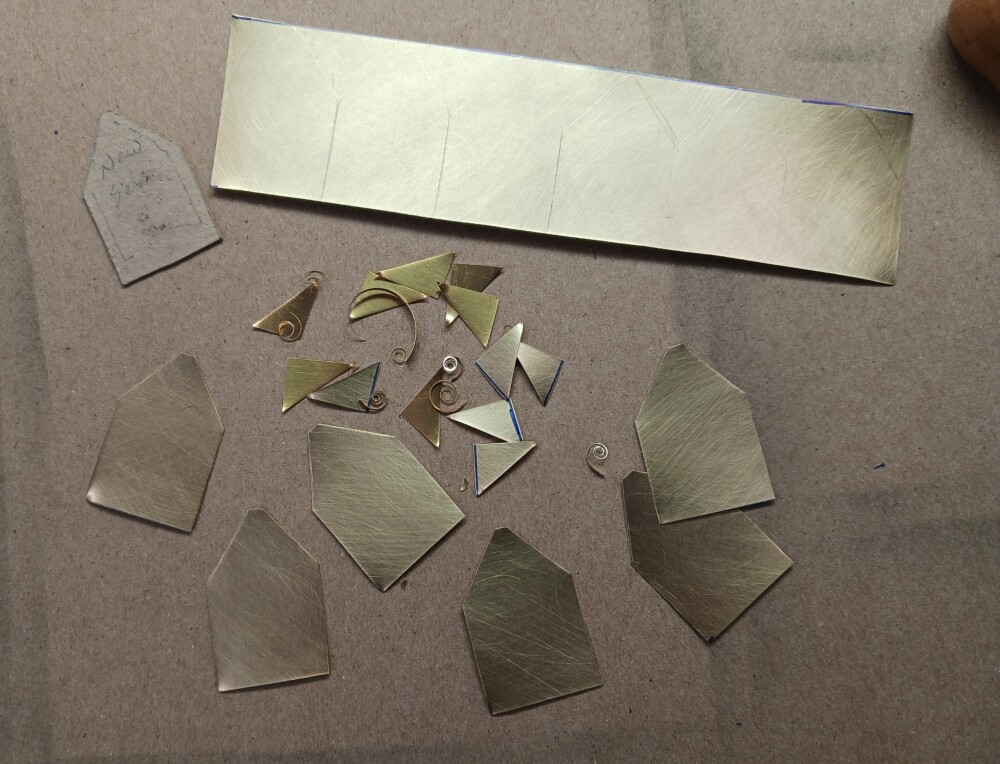

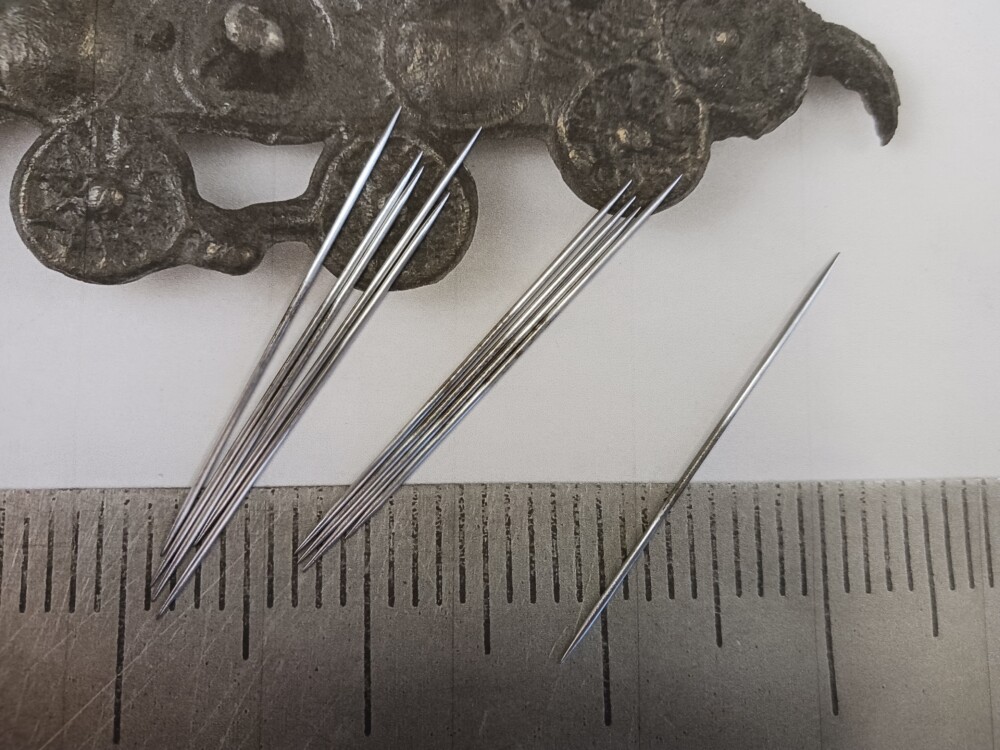

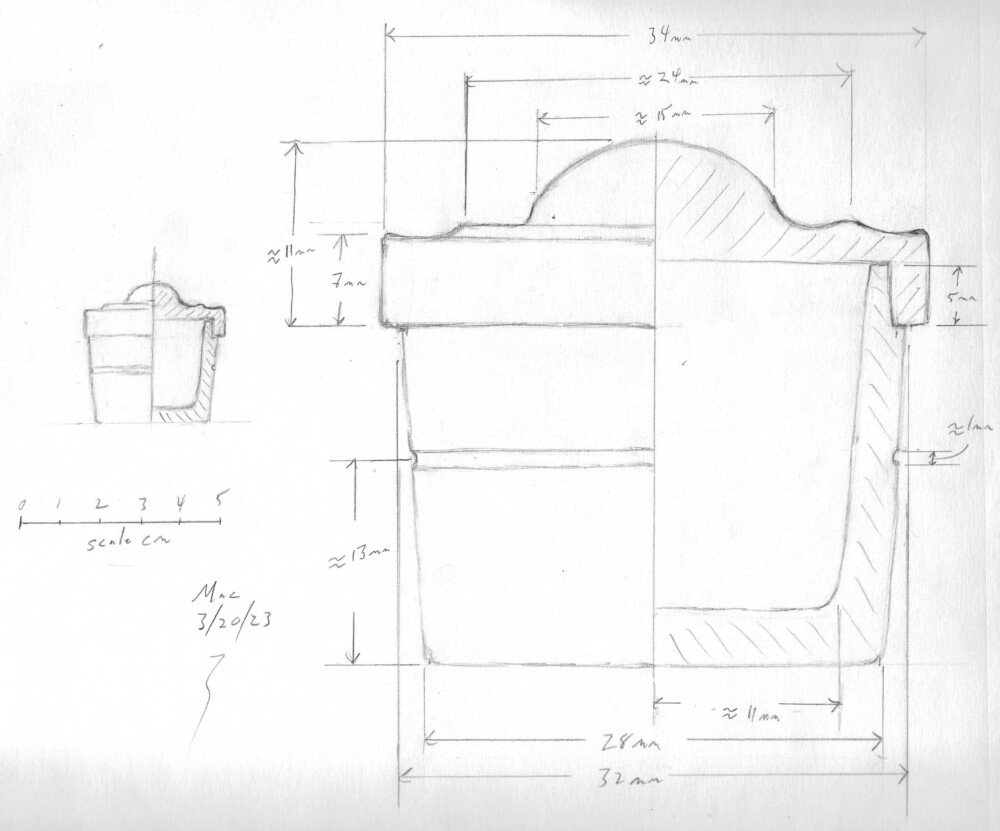

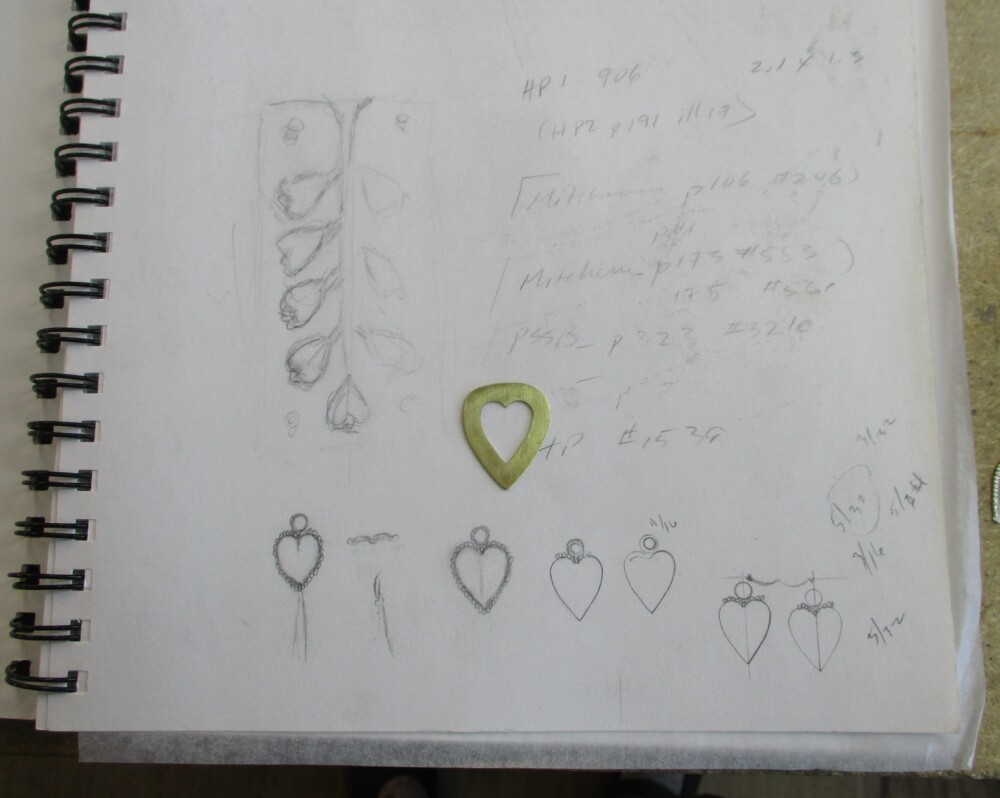

Up to now we have offered metal backings for openwork pieces where the originals have the little tongues, including many pilgrim signs, two miniatures, and one naughty item. We’ve used both brass and copper, which are easy to buy in thin sheets six inches (~15 cm) wide and several feet long. We’ve supplied the checkers (draughts) board with either red or black paper backings. We recently became interested in offering pewter backings, so we bought a rolling mill which lets us make our own thin sheet. We have experimented and decided on pewter sheet approximately 10 mils thick (10/1000 of an inch or .254 mm) for our backings. We are using copper sheet of the same thickness and brass sheet, which is stiffer, 8 mils (8/1000″ or .203 mm) thick.

I was concerned that the pewter backings might not show off the pewter openwork well. In fact, in some lighting the design is not immediately visible, but as soon you move the piece, the reflections off the various parts make the image clearly visible – and extremely striking. There is a very brief video of a sign of St. Barbara at https://www.youtube.com/shorts/eRYl24tQdIo.

Even fancier backings

Although we are not offering these options for sale, you may be interested in two of our further experiments. The first uses decorated pewter sheet. The two leaves of a small three-dimensional shrine in Salisbury (left, below) have a wrought metal sheet background with a simple pattern. We have made some exploratory pewter backings worked with a diamond pattern, like the backing for the St. Lucy sign, below right. See a video of this sign with the patterned pewter background in motion at https://www.youtube.com/shorts/KwbRvrHnPqY.

We have also faked up a colored background based on one of the diaper patterns in the Göttingen Modelbuch. These are satisfyingly gaudy and, like the pewter sheet, show best when the piece is in motion. We are still experimenting with the scale of the pattern and the colors which offer the best contrast. These offer more insights into the possible range of decorative backings for castings in the Middle Ages.

While we continue to learn more about the backings, we have started offering a range of options for our openwork pieces. Each item on our site with a backing is now photographed with backings of pewter, copper, brass, and colored paper – and with no backing at all. Check them out! You can order them with any of the metal backings – or “empty,” with a pattern so you can fit them up to suit yourself.

Be sure to share your creations to our Facebook page, or on Instagram (tag #billyandcharliepewter and #billyandcharlieDIY). We can’t wait to see what you come up with!