We were pouring some livery badges for the Belle Compagnie the other day and we ran into difficulties. Marianne made the mold in 1996 and, although it is a remarkably flat badge, which usually leads to holes and very uneven surfaces, these do not appear. This mold casts reliably, filling fully, as soon as it is warm enough.

Why is this a problem? Well, many medieval brooches, signs, and badges are cast incompletely. We do not offer products unless they are perfect (or near perfect) castings, because our modern customers have modern tastes – they are used to the uniformity of objects produced by industrial injection molding, spin casting, and pressure die casting. If we had a bin of pilgrim signs for St Adrian and in one of them the halo had not cast fully, most of our customers would keep shuffling through the stack to get a “good” one.

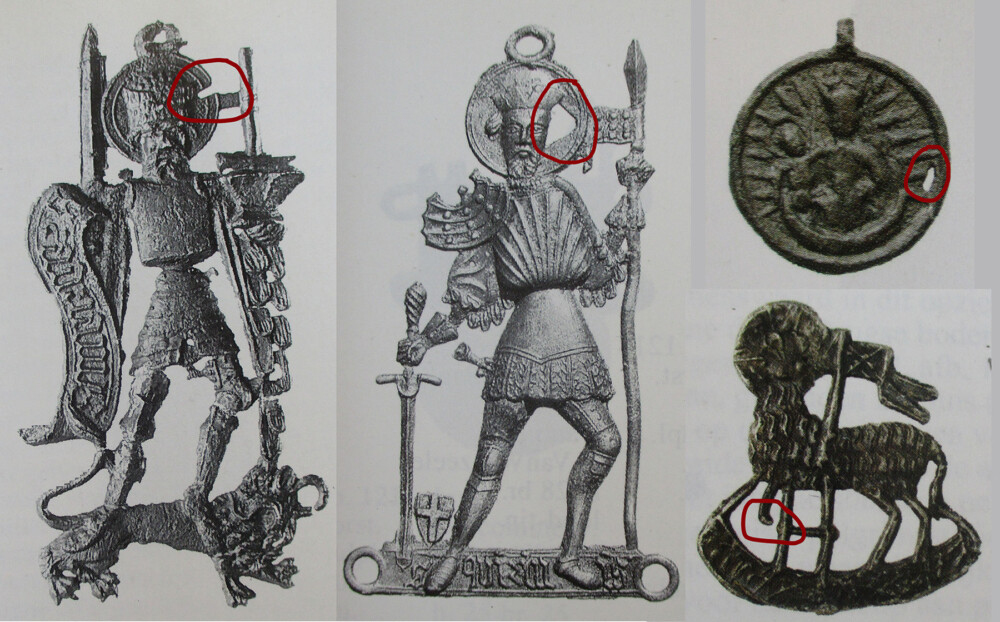

We can see from the extant historical pewter goods that the medieval customer either did not care as much or, in some cases, probably had no choice. Especially with saints’ signs acquired at holidays or festivals, it seems likely you took what you got and didn’t argue. The sign had been blessed and its spiritual value was identical regardless of the state of the casting. It didn’t matter if your saint’s halo didn’t cast or if the Virgin Mary’s medallion had a void, or if the Lamb of God was missing his knee.

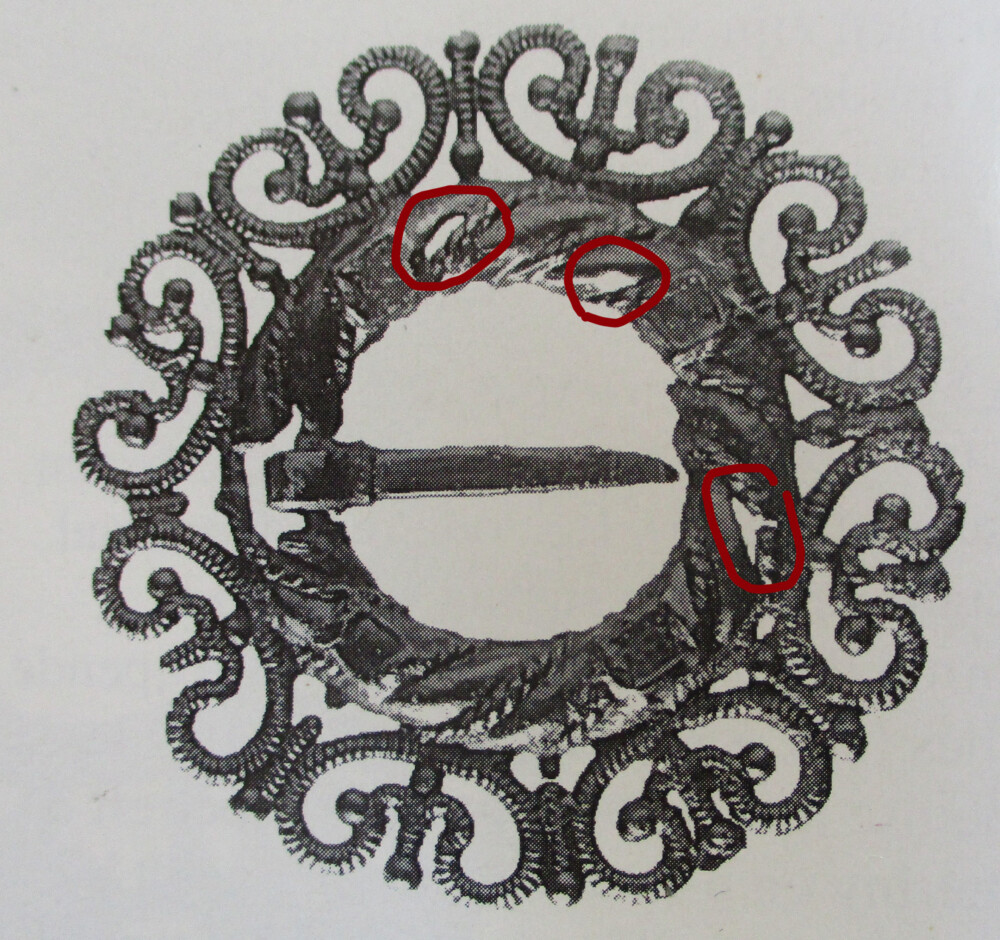

There was probably more pressure to have complete castings for decorative items, but even there we see examples that failed to fill fully, but which were pressed into use. This ring brooch has several casting voids – bubbles where the mold did not fill. Instead of being rejected, it was provided with a tongue so the brooch could be worn.

We tweak our molds for hours, sometimes working on them every time we cast them for years, so we get a lot of perfect castings. And we almost always toss incomplete castings back in the pot, rather than selling them. We do have customers who value a level of authenticity which includes incomplete castings – because they are sticklers, because it gives them a chance to talk at demos about religious practice or pre-industrial technology, because they find it amusing. In this case La Belle asked for a small number of imperfect castings of their custom mold among the complete ones, and we agreed cheerfully. That’s where the trouble began.

Mac poured the ordered badges and only managed a couple of castings where the loop at the top of the bell cast shy. He also got a few where the surface of the casting shows that the metal flow was not perfect – a place where a hole might have developed, if things were a little worse.

Marianne’s mold was too reliable; who remembers after 27 years, but she must have spent time on careful iterations to make the metal flow in as a sheet that filled the cavity evenly without trapping any air. In any case, Mac is in the habit of fidgeting as he casts to get the perfect angle, the perfect temperature, the perfect rate for the metal to enter the mold. He is really bad at doing it wrong.

So Marianne took on the task of producing “junk” castings. The most obvious way to do this is to have metal and/or mold too cold. Starting with both mold and pewter warm, but not warm enough, she began pouring. Once the mold and metal were at operating temperatures, she went back the other way – turned off the heat under the pot so the metal became progressively cooler with each pour. She did finally manage a series of castings where the bell or its loop did not fill completely.

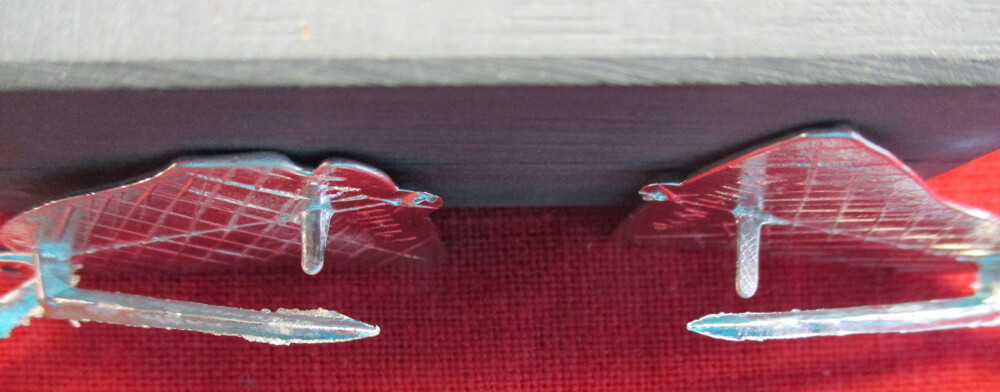

Unfortunately, in many of these castings, the retaining hook for the pin also did not cast – and no one wants a livery badge that won’t stay on. (The little tongue becomes a hook/catch for the pin; the one on the left, below, is too short.)

The easiest shortfall to create is the one Mac got, where the quatrefoil loop doesn’t cast fully. That can be produced time after time by not filling the mold to the top of the sprue so there’s not enough pressure to send the metal up into the loop. Here’s a selection of castings, starting with a near miss at left (the loop almost closed) and ending with a couple of pitiful stubs.

The failure to fill the rim of the bell to the edge is trickier – Marianne had to press one of the halves of the mold back down hard while letting the other side fill normally. This incidentally led to some casts where the loop was very flashy, but that is hardly a defect, since the flash is easily removed.

This did produce incomplete casts with crinkly edges. And the surfaces were often not what we prefer. But she never got the requested holes. Her rogues gallery of usable, but incomplete casts:

We’ll see which of these the Compagnie likes and which are just too much. Meanwhile, we’ll finish up with a thought experiment about the Middle Ages: You’ve heard of re-enacting groups having a five-foot (two-meter) standard for authenticity – if it looks authentic from five feet, it’s okay. For pewter livery badges you might employ a ten-foot (three- meter) rule. From that distance you should be able to tell what the badge depicts well enough to identify whose livery it is. If you can’t, the lord needs a new device – or a new badge. If you can, even if the casting is incomplete, it’s okay!