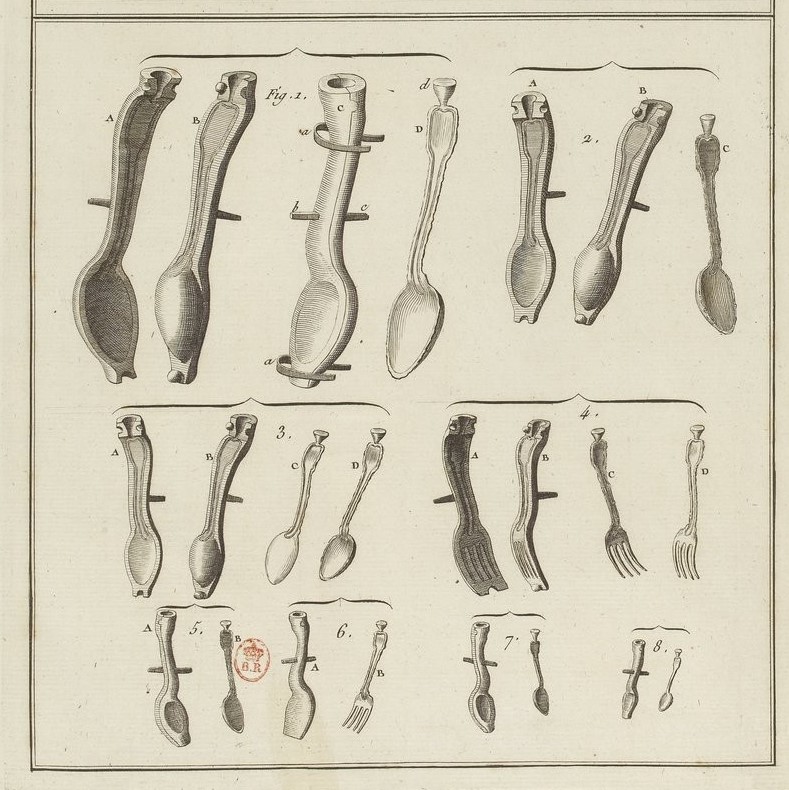

We have been wanting to make a larger, round, slush-cast bell. (Are you new to slush-casting? See the very end of this post for a brief explanation – then come back to the top!) Mac worked on the project off and on for several years. There are similar bells from London, Valenciennes, and the Netherlands. There are also (almost) two 13th-century molds (with both mold halves present) for casting them. Why almost? One of the molds has been lost, but sometime before that happened, the owner cast it, so a record of the cavity remains.

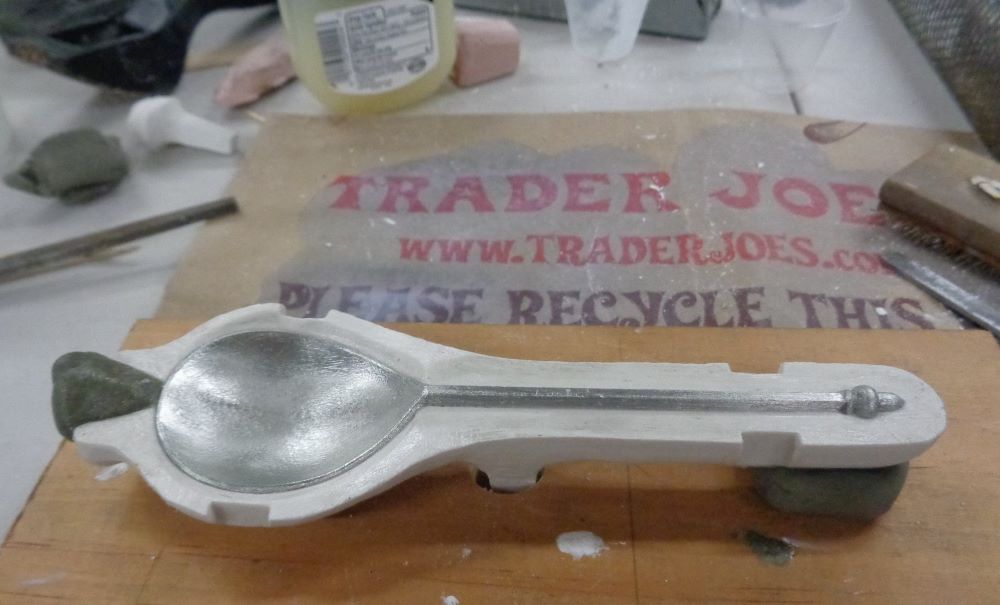

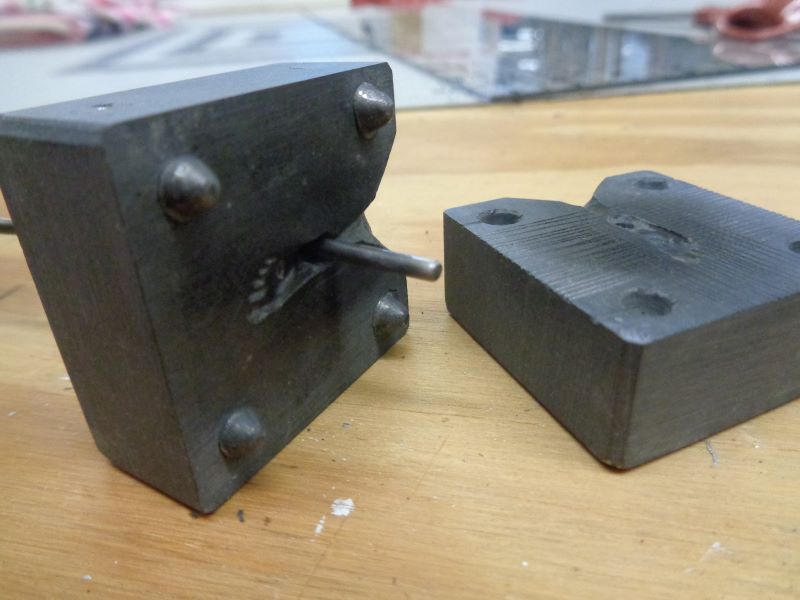

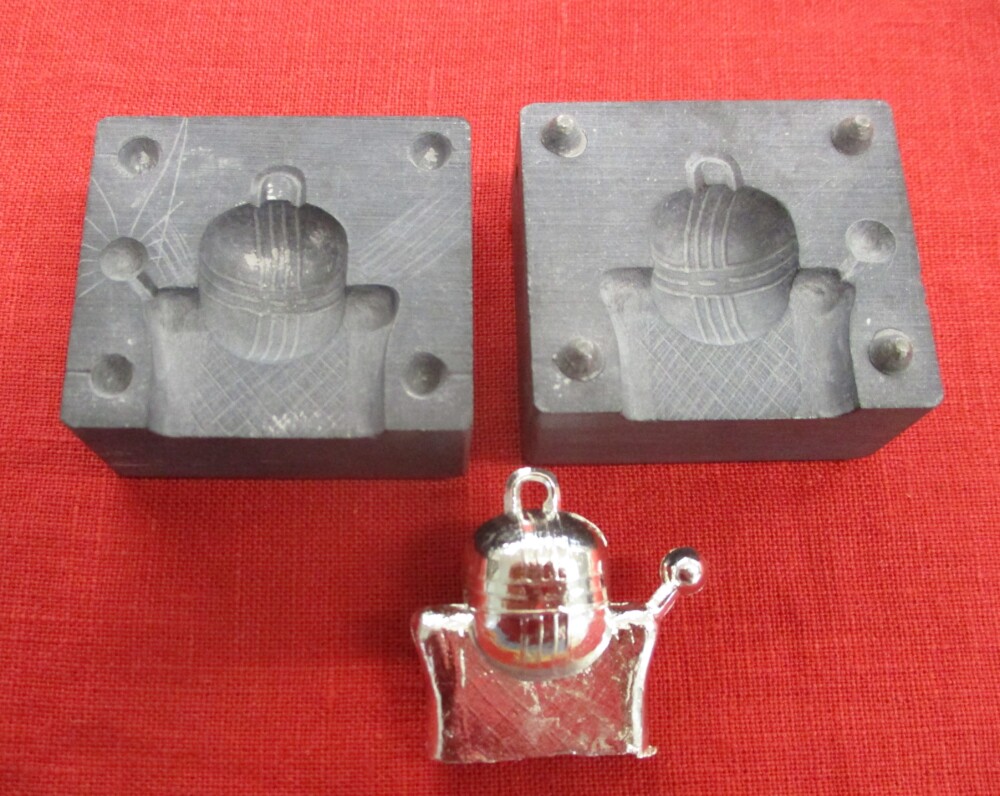

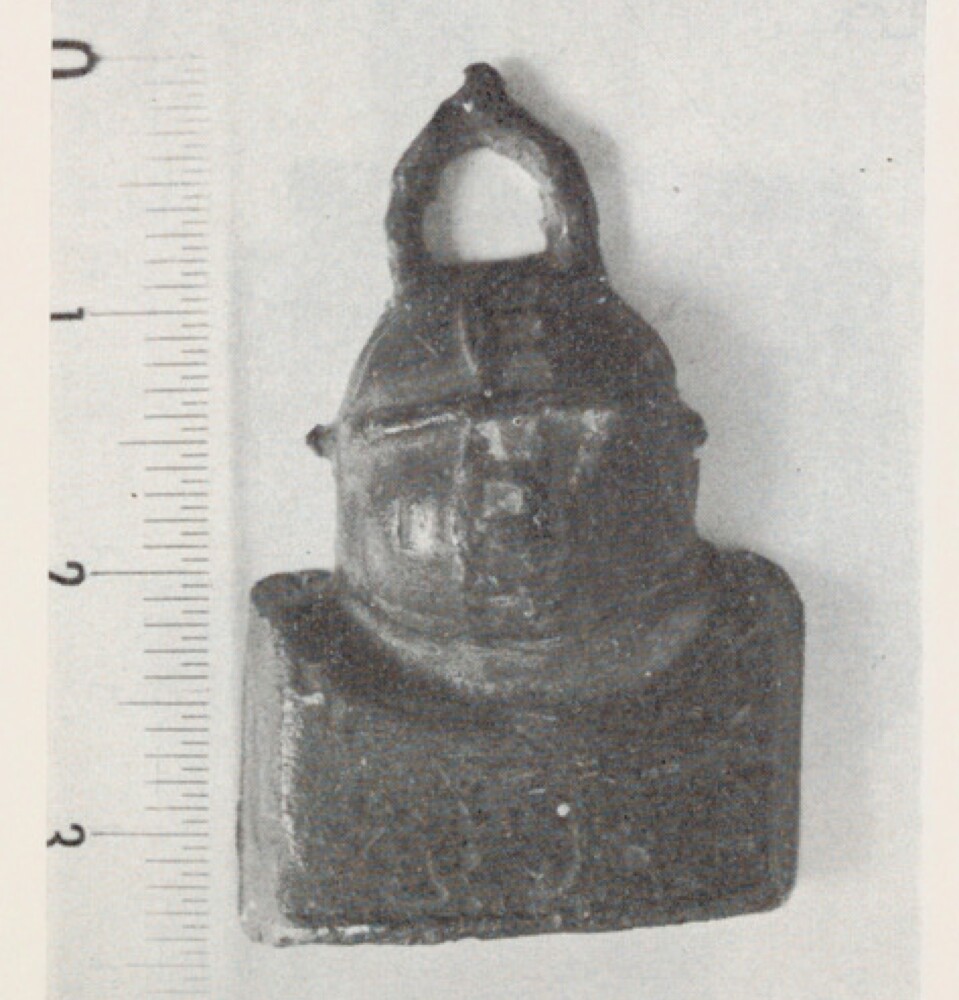

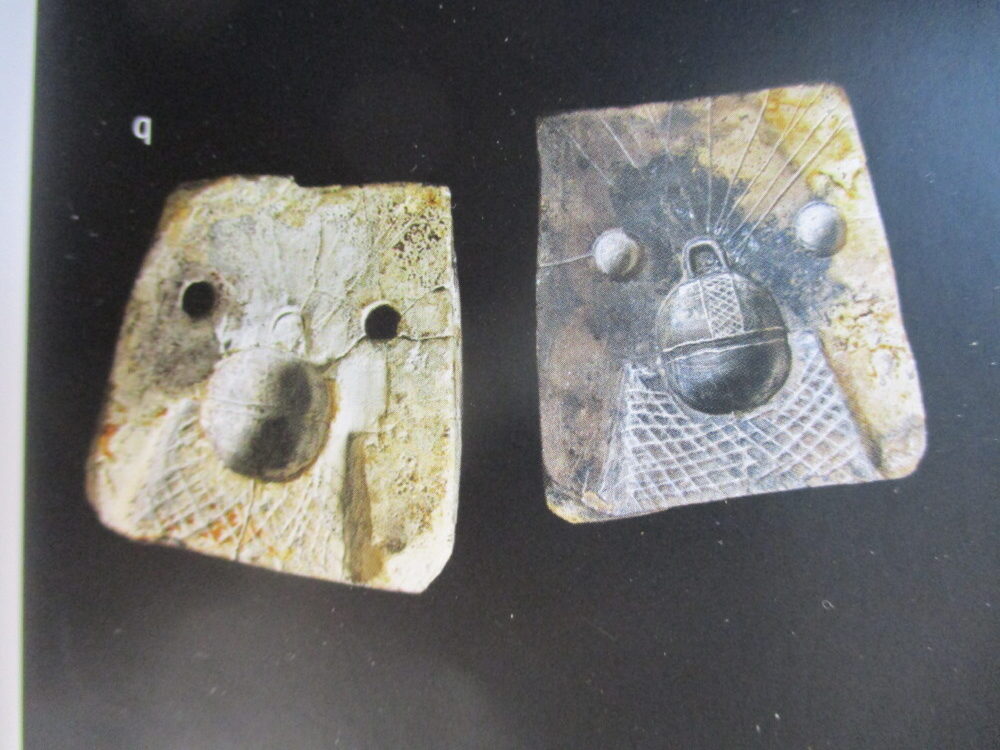

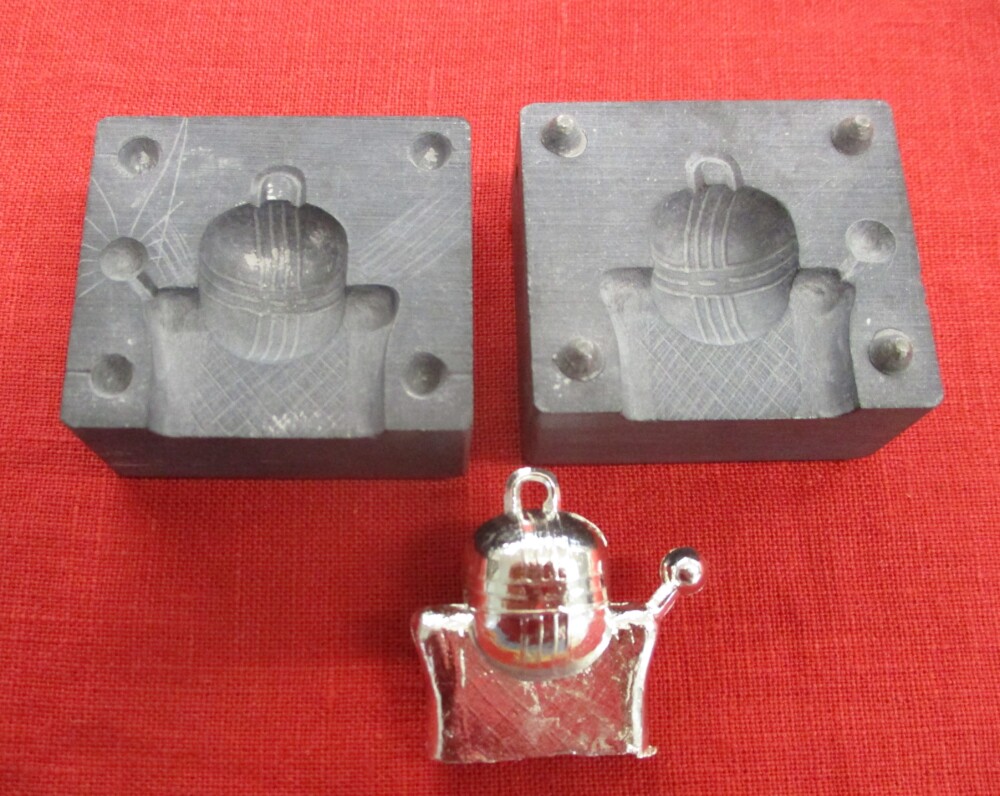

The mold on the left was found in Rostock, Germany (published in Berger, 2020, vol. 1, p.136). The lead casting in the middle was made of a mold found in the area of the medieval market and artisan quarters in Rocamadour (Rocacher, J. 1980. Les mouliers de Rocamadour. Bulletin de la Societé des Études de Lot, October–December. 284–92.) On the right, our mold.

We only knew the Rocamadour casting at first and it misled us into thinking that the mold had a core – a carefully fitted piece of wood, for example, that held the bottom of the bell open. We imagined that the tin was poured into the loop and thence the bell while the core was in place, then the core withdrawn to drain the still-molten center of the casting. This was wrong – it was impossible to get enough metal through the loop and, although we do have molds that fill at one end and drain from the other (the horn whistle, the toy ewer, and the hollow domed button), it didn’t work here.

The mold from Rostock makes it clear that the square opening is the gate for both filling and emptying the mold. The shape leaves a opening of even width once the gate is cut away, and the bell can then be cleaned up and finished. Mac’s final mold (the earlier ones were altered beyond recognition in experimentation) works the same way. It casts the “pea” at the same time.

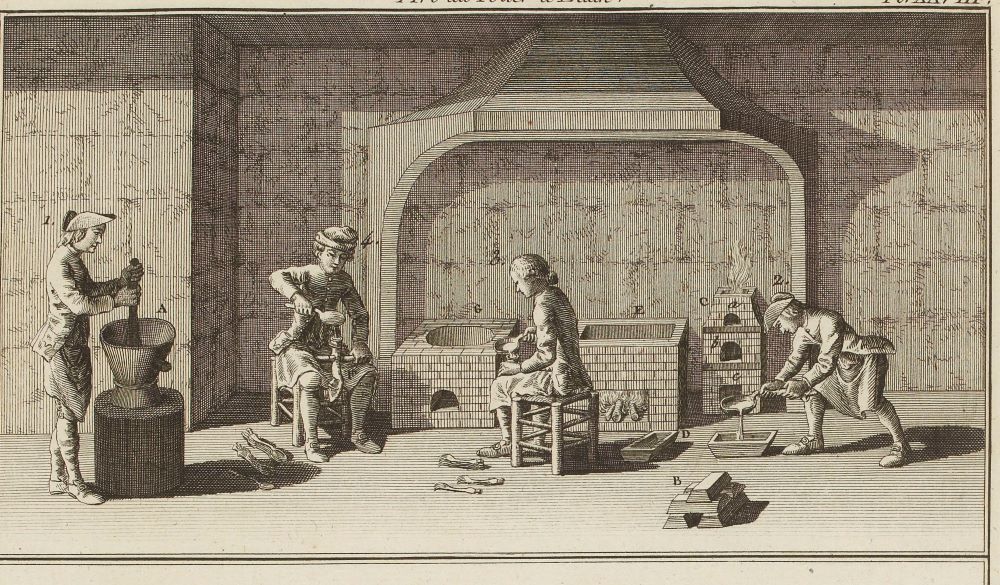

To pour the bell, we fill the mold to the top with pure tin. After a short length of time (Mac counts seconds, depending on the temperatures of the metal and the mold, and also sloshes the metal back and forth to see whether the shell is forming) he pours back the still molten metal from the center of the bell.

The bell comes out with a square, hollow sprue. The sprue in the middle photo is unusually baroque. We clip the “peas” off.

We melt the excess sprue back into the metal in the casting ladle. We think a hot iron is probably a more authentic means of removal, but that is not convenient in our studio.

We trim along both sides of the bell to remove the sprue.

After a quick trip across the grinder (not illustrated), we drop a pea in each bell and squeeze it closed. The completed weight of the bells ranges between ~.29 and .37 ounces/8.25 and 10.5 grams (from a quick weighing of about a dozen sample bells).

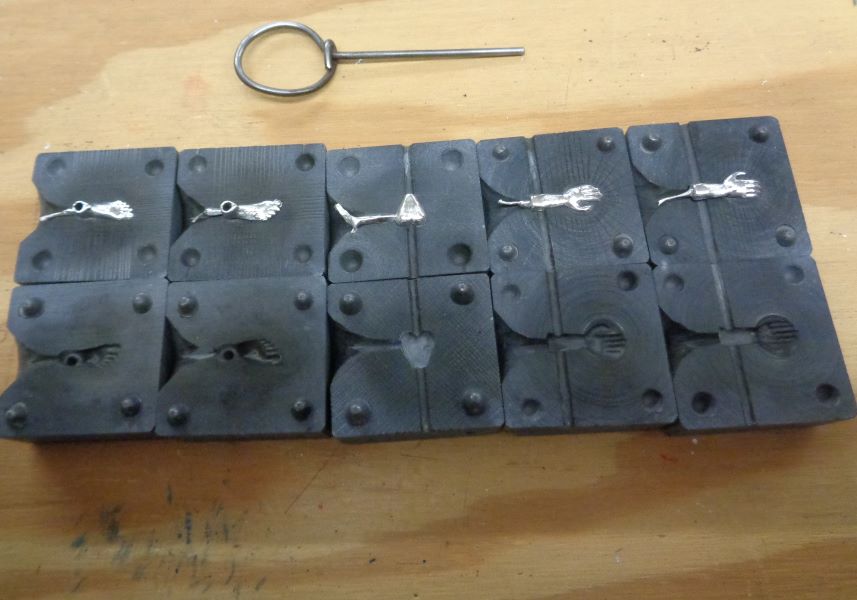

Slush casting is used to make hollow objects – ampullae, whistles, toy cooking pots, three-dimensional figures. We have about two dozen items made this way. The molds have large openings and you pour the metal in, wait for it to become solid around the edges, then pour out the metal that is still liquid, leaving a shell. Often there is one gate, which you pour both in and out of. Sometimes there is a gate to fill the mold, and a different gate to empty it. We made a video of Mac pouring the toy cooking pot with lid that shows the process – check it out on Youtube!

Slush casting only works when the metal has a distinct melting point – it is liquid or it is solid. Pure lead and pure tin were the metals used in the Middle Ages to make this sort of object. We, of course, stick with tin. Alloys do not slush-cast well. The various melting points of the different metals in an alloy mean that over large temperature ranges the alloy is not either liquid or solid, but is sort of like grainy, wet sand – and it will not empty the mold.